Among the many phenomena, worthy of mentioning in context of the history of Eastern civilization, perhaps the most astonishing is the fact that Armenia – continuously called the cradle of civilization – was the first country in the world where Christianity became the official state religion. It began at the start of the 4th century (301). This fact also had serious consequences for the evolution of art in these areas and the development of new forms based on the traditions of the art of the ancient state of Urartu, very strong influences of the art of the Persian Sassanids and close contacts with the art of Syria. The adoption of Christianity caused, above all, the need to build churches for the faithful and monasteries for the clergy. Most of the Christian temples preserved to this day or traces of them found, the latest catalog of which includes 460, were built between the beginning of the 4th century and the 7th century.

These were mostly churches erected on a tetraconch plan with four apses or on a Greek cross plan, with a dome resting on squinches. Just as often, probably under the influence of Syrian architecture, starting from the 5th century appeared basilicas on square or rectangular plans. Structures shaped this way were richly decorated with sculptures and bas-reliefs made of stone or stucco, placed around window openings, around portals, in the form of friezes, or with ceramic cladding filling the panels. Sculpted and bas-relief figural scenes were decorated with arabesques and geometric ornaments derived from arabesque forms often appearing right next to each other and covering as much space as possible. In the art of Armenia, there were both traditional forms adopted from the art of Urartu, ancient Persia, and new ones, derived from Hellenistic art, which made their way there through fabrics and ivory plates. As early as in the 4th and 5th centuries, plant ornaments in Armenian art were being transformed, creating an extraordinary wealth of forms, from naturalistically treated vine coils to geometric, abstract spiral shapes. On the other hand, figural representations, both sculptural and related to miniature painting, used iconographic schemes taken from Byzantine art. An individual phenomenon that was born and developed in Armenia, becoming a typical form of expression for Armenian artists, are slabs in the form of standing stone rectangles with carved crosses, called khachkars.

The first khachkars were carved in wood, however starting from the 4th century only stone was used to create this work of art. They were forged to commemorate someone's important deeds and achievements, also to emphasize the importance of political events, foundations, military victories, private events in the life of the founders, and they were also used as tombstones. Khachkars were placed everywhere: in the walls of churches, both external and internal, on the roofs, by the roads and on the walls of secular buildings.

The first khachkars were carved in wood, however starting from the 4th century only stone was used to create this work of art. They were forged to commemorate someone's important deeds and achievements, also to emphasize the importance of political events, foundations, military victories, private events in the life of the founders, and they were also used as tombstones. Khachkars were placed everywhere: in the walls of churches, both external and internal, on the roofs, by the roads and on the walls of secular buildings.

They were richly decorated with arabesque and geometric ornaments, appearing side by side and interpenetrating each other, which symbolically emphasized the reference to the idea of infinity and eternity. The lower part of the slab under the cross or the side parts were very often covered with inscriptions containing precise information about who, when and why founded the church; they are therefore also a stone book of the history of Armenian society. Thanks to such an inscription, we know that in the 17th century there lived an Armenian who made and decorated tents in Lviv.

A new stage in the development of Armenian art took place when the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia was established in the 11th century, which was placed in today's southern Turkey until 1375. Most Armenian artists also moved there. Their work was shaped by contacts with Christian Europe and also influenced by Arab, Byzantine and Turkish Seljuks art. As a result of the permanent political destabilization of the state, due to which the culture of the bourgeoisie did not stand a chance to develop properly, Armenian art in the period of the Cilician Armenian kingdom developed mainly in monasteries; therefore, the main domain was miniature painting, which became, next to the khachkars, the most important field of expression of Armenian artists. By decorating liturgical books copied in monastic scriptoria with miniatures of the highest artistic level, the Cilician monks gave evidence of their deep Christian faith and devotion to the church.

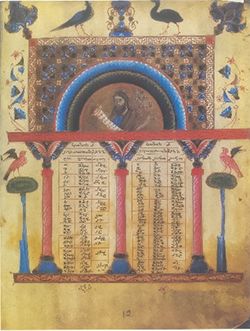

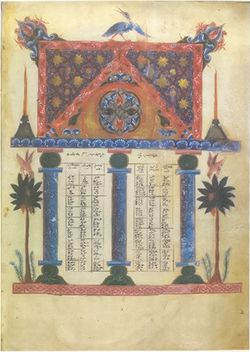

Over the centuries, they have made an enormous number of books. The corpus of preserved illuminated Armenian manuscripts includes 24,000 manuscripts, of which about 3,000 are dated to the period between the 11th and 18th century. In addition to perfect workmanship, Armenian miniatures attract attention with their unusual iconographic schemes. Thus, for example, the influence of Sassanid art transferred through textiles is visible in the way animals and birds are depicted. A curious fact is that Arabic Kufic letters were sometimes used, single or in the form of an ornament, as a kind of decoration. The first pages of the Armenian Gospel Books are filled with a series of ten Tables of Canons composed by Eusebius of Caesarea (ca. 260-340). The texts are arranged in boxes between two, three or four columns, which are joined by arcs to form an arcade. The columns supporting the arches and the fillings of the area above the arcades are decorated thoroughly with ornaments including complicated, small drawings, sometimes introducing the images of the Church Fathers, the Evangelists or the picture of the author of the Tablets. Based on the comments to the Tablets, a system of mystical meanings associated with their contents was created. The basic meaning of the columns supporting the arcades was related to comparing their role to the role of the Tablets in the organization of church life.

Over the centuries, they have made an enormous number of books. The corpus of preserved illuminated Armenian manuscripts includes 24,000 manuscripts, of which about 3,000 are dated to the period between the 11th and 18th century. In addition to perfect workmanship, Armenian miniatures attract attention with their unusual iconographic schemes. Thus, for example, the influence of Sassanid art transferred through textiles is visible in the way animals and birds are depicted. A curious fact is that Arabic Kufic letters were sometimes used, single or in the form of an ornament, as a kind of decoration. The first pages of the Armenian Gospel Books are filled with a series of ten Tables of Canons composed by Eusebius of Caesarea (ca. 260-340). The texts are arranged in boxes between two, three or four columns, which are joined by arcs to form an arcade. The columns supporting the arches and the fillings of the area above the arcades are decorated thoroughly with ornaments including complicated, small drawings, sometimes introducing the images of the Church Fathers, the Evangelists or the picture of the author of the Tablets. Based on the comments to the Tablets, a system of mystical meanings associated with their contents was created. The basic meaning of the columns supporting the arcades was related to comparing their role to the role of the Tablets in the organization of church life.

The layout of the ten Tables symbolically means ten holy places, ten tents, ten tabernacles where God is present. The next part is followed by the Gospels, each of which begins with a full-page miniature depicting one of the four Evangelists. In most manuscripts, the beginning of the text of the individual Gospels, written in the Armenian script style: notrgir, bolorgir, erkat'agir or sełagir, is an ornamental initial formed from the symbol of one of the Evangelists. Often the text is preceded by four miniatures depicting scenes from the New Testament: Annunciation to Zechariah, Annunciation to Mary, Homage to the Three Kings, Baptism of Christ, symbolizing the epiphany - the revelation of Christ. The perfected skills of painting miniatures and forging ornaments were brought by the Armenians to Istanbul, Crimea, Western Europe, Persia, South-East Asia, the Balkans and Poland, to the countries where they had to live for hundreds of years in the diaspora.

The layout of the ten Tables symbolically means ten holy places, ten tents, ten tabernacles where God is present. The next part is followed by the Gospels, each of which begins with a full-page miniature depicting one of the four Evangelists. In most manuscripts, the beginning of the text of the individual Gospels, written in the Armenian script style: notrgir, bolorgir, erkat'agir or sełagir, is an ornamental initial formed from the symbol of one of the Evangelists. Often the text is preceded by four miniatures depicting scenes from the New Testament: Annunciation to Zechariah, Annunciation to Mary, Homage to the Three Kings, Baptism of Christ, symbolizing the epiphany - the revelation of Christ. The perfected skills of painting miniatures and forging ornaments were brought by the Armenians to Istanbul, Crimea, Western Europe, Persia, South-East Asia, the Balkans and Poland, to the countries where they had to live for hundreds of years in the diaspora.

According to sources, Armenian colonies in Polish cities such as Lwów (Lvov), Łuck and Kamieniec Podolski, existed already in the 14th century. In the 16th century, Armenians also came to Bar, Tyśmienica, Podhajec and Zamość. Smaller groups of Armenians came to Poland even earlier. In the cities where they settled, they built churches. One of the first was the cathedral - first dedicated to the Dormition of the Blessed Virgin Mary, then to the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary - in Lvov, founded in 1363 by emigrants from Ania, built on the model of Crimean churches, particularly close to the architectural style of the church in Kaffa.

Despite later alterations, it retained much of its original appearance. Early Armenian foundations also owned the church of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary - according to some sources from the 13th century - as well as the church of St. Nicholas from 1398 in Kamieniec Podolski and the church in Jazłowiec dedicated to the Mother of God.

Despite later alterations, it retained much of its original appearance. Early Armenian foundations also owned the church of the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin Mary - according to some sources from the 13th century - as well as the church of St. Nicholas from 1398 in Kamieniec Podolski and the church in Jazłowiec dedicated to the Mother of God.

In the 17th century, the construction of the Armenian church in Zamość which started at the end of the 16th century, was completed. The appearance of these churches is described in written sources, drawings and fragments of architectural details with rich sculptural decoration. On the other hand, the Armenian churches built in Bar, Tyśmienica, Podhajce, Stanisławów, Kuty, Brzeżany, Czerniowce, Horodenka, Śniatyn, Łysiec, some of which have survived to this day, did not stand out with anything special. These were typical eighteenth-century buildings with rather modest shapes, often with a single nave.

These churches, as well as the remains of Armenian architecture and architectural details preserved in Lvov, Kamieniec Podolski and Jazłowiec are a testimony to the adaptation of general concepts to the tradition of local architecture, while maintaining a different form of decoration.

These churches, as well as the remains of Armenian architecture and architectural details preserved in Lvov, Kamieniec Podolski and Jazłowiec are a testimony to the adaptation of general concepts to the tradition of local architecture, while maintaining a different form of decoration.

In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, kings and magnates granted Armenians numerous privileges securing their interests. Thanks to this, they were able to conduct trade and craft activities, although until 1630, when the Armenian church officially accepted the union with the Roman church, they were not equal in rights with Poles. Acceptance of the union took place in an atmosphere of reluctance among some part of the Armenian community, it became the cause of many disputes and discussions, as well as comments from Polish Catholics and representatives of the clergy, who believed that the Armenians, despite the union, are not "unum cor". The union of the Armenian Church with the Roman Catholic Church was of great political importance for Polish Armenians, playing a decisive role in the process of their integration with Polish society. The Armenians who did not approve of the union left Poland, while the rest reconciled themselves to the reforms.

The union concerned primarily the spiritual life and the rite of the Armenian church in Poland. Before the union, Armenian religious ceremonies were based on rules transferred from Etchmiadzin, mostly contained in Armenian liturgical books brought from Armenia. As Latinization progressed, liturgical clothing and apparatus became less and less different from those used in the liturgy of the Roman church. Precise information about the clothes used in the Armenian church was provided by the municipal court books with the records of Armenian councilors from 1649 to 1713, which also included inventories of equipment and apparatus of the Armenian cathedral from 1687, in a depleted state, after the contributions of three sieges. These garments were famous for their Eastern magnificence and splendor. In some of the notes written by Jan Alembek, among the chasubles in the Armenian cathedral, we find "old-fashioned cuts'', which were supposed to be "not cut but round (habent ornatus non scissos sed omniquaque rotondos)", and chasubles representing "Polish cut" made of rich fabric of golden threads (in Polish the fabric is called “Złotogłów''), altembas, telet, tabin, satin and other precious textiles. There were also "books, chalices and other fine old Christian liturgical equipment (Christianorum veteranorum splendidum suppelectilem"). Among these notes, on the occasion of the report on the dispute between the archbishop who lent the robes for Toros Bernatowicz's funeral and did not want to return them to "schismatic makeshifters and Armenian senators'' Krzysztof Zachariaszowicz and Krzysztof Tomanowicz, the following were mentioned: "the episcopal miter with precious stones and pearls planted; chasuble made of rich fabric of golden threads with amice decorated with precious stones, diamonds, rubies and pearls; an altembas chasuble with a velvet amice with pearls and gold pontals, an altembas bishop's pallium set with pearls; the deacon's dalmatic with pearls; great silver-golden cross (Pax); a tincture with golden basin; a golden chalice with a velum set with pearls and the Gospel written on parchment, bound with silver.” Władysław Łoziński mentioned “old” chasubles referring to the garments preserved in the Armenian cathedral, with crosses made of gold plaques and figural embroideries placed on them. One of these chasubles was embroidered with the image of the four Evangelists, while the other was embroidered with the scene of the Crucifixion. Worth mentioning are the notes on two altembas chasubles, which, according to the information, were "with Arabic letters", i.e. inscriptions that also served as a decorative ornament. Among the mitres, the records singled out an "old-fashioned" one, all of drawn gold, which had "embroidered pearl tassels." The richest and most expensive decorations were the amices, called warszamaki. They were made mainly of velvet, decorated with golden crosses and pearls, with images of the Apostles, St. Helena, Salvator, the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Angels.

The Armenians brought liturgical books with them to Poland, which were copied in Lviv, Zamość, Kamieniec Podolski and Jazłowiec. Those writings were significantly dispersed as a result of World War II, and are now in the collections of Paris, Vienna, Eczmiadzin, Warsaw, Cracow and Wrocław.

Armenian artists rarely engaged in easel painting. The representative of the family of Armenian painters in Lvov was Jan Boguszowicz, son of Paweł Bogusz and Elżbieta Axentowiczówna, brother of Szymon, author of, among others, a portrait of King Sigismund III. This painting is painted flat, the features are marked with a hard contour, which gives the face with large dark eyes an oriental character. This impression is also supported by a large number of detailed painted jewels, contrasting with a flat, uniform background.

Armenian artists rarely engaged in easel painting. The representative of the family of Armenian painters in Lvov was Jan Boguszowicz, son of Paweł Bogusz and Elżbieta Axentowiczówna, brother of Szymon, author of, among others, a portrait of King Sigismund III. This painting is painted flat, the features are marked with a hard contour, which gives the face with large dark eyes an oriental character. This impression is also supported by a large number of detailed painted jewels, contrasting with a flat, uniform background.

The source of these original stylistic features can be attributed to the formal independence resulting from the tradition of Armenian art. On the other hand, the images of Our Lady worshiped in Armenian churches were copies of the images of Our Lady of Częstochowa and Our Lady of Piekary, as exemplified by the images from the eighteenth-century altars in Armenian churches in Stanisławów and Łysiec, today in Armenian parish churches in Gdańsk and Gliwice. One of the most venerated images of Mary by the Armenians was the image of Our Lady of Jazłowiec. According to legend, the painting was created in 1424. In 1676, when the Turks seized Jazłowiec, some Armenians fled to Brody, taking it with them. In Brody, he was placed in a Latin church where services for the Armenians were held. After the fire of the church, from which the painting was saved, it was stored in Marek Nikorowicz's shop, "where the lamp was lit day and night, because people praying before it experienced many graces and consolations in their needs." After 1700, the Armenians from Brody moved to Lviv with the miraculous painting. In Lvov, the painting was placed in the Armenian cathedral.

In the cities, Armenians were mainly engaged in trade and arts and crafts. They were known primarily as goldsmiths, embroiderers, and kurdybannicy (craftsmen who specialized in leatherwork). They also tried other crafts. It should be noted here that as artists-craftsmen they maintained their formal independence for the longest time, continuing the original traditions of Armenian art. On April 30, 1583, Chancellor Jan Zamojski issued a privilege for the Armenians, under which they were able to “perform their games, trades and crafts” in Zamość. Zamojski said: “I give them equal rights with other inhabitants”. On May 24, 1585, Murat Jakubowicz, who came from Kaffa, received a privilege from Chancellor Jan Zamojski, confirmed by the king, for complete exclusivity in the production and sale in Zamość of carpets woven in the Turkish pattern, "more Turcico", and saffiano and embossed leather. However, as early as in 1605, the whole enterprise collapsed, as Chancellor Jan Zamoyski stated in his parliamentary speech, as a result of the competition of merchants who temporarily lowered the prices of imported products and made the manufacture in Zamość unprofitable.

In 1685, King Jan III Sobieski issued a privilege for Armenian goldsmiths. In craft workshops in Lvov and Zamość, they used goldsmithing to decorate scabbards and saber hilts, parts of saddles, bracers, bulavas, quivers. Subsequently, they assembled these parts with parts brought from the East and sold them in their own stores or through other Armenians. They adorned them with intricate Eastern patterns, small nacre plaques inlaid with gold wire and stones. The most characteristic motifs - often repeated and taken from Islamic art - are: a rosette surrounded by leaves in a swirling arrangement, swirling rosettes and frontal flowers with three or two symmetrically arranged leaves, against the background of medallions.

Armenian embroidery in Poland has a tradition dating back to the mid-sixteenth century. As early as 1552, King Sigismund August welcomed three Armenian embroiderers to his court. Documents concerning Zamość in the 17th century mention several embroiderers by name. In 1658, a privilege was issued for Armenian embroiderers in Lvov. As Tadeusz Mańkowski wrote, Jan Bogdanowicz, bearing the title of His Majesty's embroiderer, was the promoter of issuing the statute. Pursuant to the regulations, they could have their own stalls, where they were allowed to sell products as members of the guild: "embroideries on leather or saffiano, saddlebags, quivers, shields, felts, quilts and other items belonging to soldiers''. Apart from male embroiderers, the Lvov files also mention women: Hadziewiczowa and Eminowiczowa. Embroidery in Lvov must have developed well, which was certainly caused by a large demand for Armenian embroidery. Probably as a result, in 1665, the Lvov magistrate granted the embroiderers further rights.

Armenian craftsmen gained real fame with the production of silk belts, which in Poland were called "kontusz" belts.

Armenian craftsmen gained real fame with the production of silk belts, which in Poland were called "kontusz" belts.

On July 10, 1678, Jędrzej Potocki issued a privilege in Stanisławów, under which "craftsmen of all crafts of the Armenian Nation no longer have to belong to the Polish guild, but they can have their own constituere" . In the first half of the 18th century, Dominik Misiorowicz was active there but later on moved to Brody where he devoted himself to making belts of Istanbul and other rich goods. The second Armenian master, known by name, active in Stanisławów was Jan Madżarski, to whose studio in 1757 Michał Kazimierz Radziwiłł sent two of his subjects from Nieświęt to study the belt-making. A year later, Madżarski left Stanisławów and moved to Niewierz. There, in 1758, he made a deal with Michał Kazimierz Radziwiłł, for making: “tapestries, shabracks, belts with flowers, numbers, gold, silver and silk according to the given outline.” . He also committed himself to “teach the boy perfectly this Persian work”, which shows his willingness to teach his craft. In 1767, Jan Madżarski moved to Słuck, where in the years 1767-1776 he made as many as 758 belts for the needs of the Radziwiłł court. Around 1780, Jan's place in the workshop was taken by his son, Leon Madżarski, who in 1790 was ennobled for his merits in introducing industry and handicraft in the country.

In the Slutsk fabric workshop, the belts were signed. The signatures were subject to changes along with the changes of the factory managers. During the period of running and leasing the factory by Jan Madżarski, in the years 1767-1780, the belts were marked: "Słuck", "Me fecit/Słuciae"; “Me fecit / Słuciae Jan Madzarski”. In later years, 1780-1787, when the manufactory was leased and run by Jan's son Leo Madżarski, the signatures were woven in Cyrillic: “Leo Ma/żarskij”; “W gradie/Słuckie”; “F.K.S.R./Słuckie”; “Słuckie”. For custom orders, silk fabrics were also made, interwoven with gold or silver metal threads, with various floral patterns similar to the patterns used in decorating the belts. The most popular motif was the one imitating carp scales.

Paschalis Jakubowicz - who came from Tokat in Anatolia - in Warsaw ran the so-called Turkish shop with eastern goods. He received the citizenship of Warsaw and Cracow, where even before 1787 belts were made for his Warsaw shop. As early as around 1788, Paschalis established belt-making workshops in Warsaw, which in 1789 were already so developed that he could announce his services in “Gazeta Warszawska” (Warsaw’s Newspaper), advertising that everyone can order a belt from him “in whatever kind and style” . Almost at the same time, Paschalis founded a large manufacture in Lipków near Warsaw. In 1791, for "multiplying useful handicrafts", he was ennobled and adopted the surname Jakubowicz, the Jakubowicz I coat of arms, a variation of the Junosza coat of arms, depicting the Paschal Lamb with a flag. The family tradition was continued by his son Józef Paschalis Jakubowicz. The belts from the Paschalis factory were signed in the corners of each head, first with the surname, then with the Jakubowicz coat of arms.

However, the activity of the Armenians in the Commonwealth fades when we compare all its fields with trade, which - as in the entire diaspora - they dealt with especially dynamically from the end of the 16th century. Szymon Lehaczy (Symeon Lechac'i - from Lechistan), an Armenian living in Poland at the beginning of the 17th century, the author of memoirs from a trip to the Holy Land, wrote that “among them [the Armenians] there are no craftsmen, instead they are all great and wealthy merchants, they have their wekils [representatives, agents] in Istanbul, Ancuria, Ipahan, Moscow, Gdansk, Portugal and elsewhere...” . Therefore, they moved between Poland and the countries of the Orient, usually for trade purposes, but also as interpreters and royal envoys, agents and couriers. They significantly influenced the growth of interest in the Orient among Poles, delivering goods from there and in this way they greatly contributed to increasing the stock of Eastern art in Poland.

The range of trade and the quantities of eastern goods imported to Poland by Armenian merchants are provided by source references. Zachariasz Iwaszkiewicz, for example, in 1600 brought from Istanbul to Lviv “30 bales of camlet [soft fabric made of camel or goat wool] for 9000 ducats, 150 carpets for 775 ducats, belts called from Bursa for 340 ducats, one bale of silk for 1050 ducats” . On the other hand, for another merchant from Lviv, the caravan in 1602 brought, among others, several dozen bales and saddlebags of muchair [thick fabric made of goat hair] and carpets for the price of 14,992 zlotys” . A different Armenian merchant, Andrzej Torosiewicz, received a transport of 340 pieces of silk belts from Istanbul.

In addition to those mentioned, the items of trade were elements of weapons and armaments. This is clear from the lists of movable property of Armenian merchants in Zamość, preserved from the 17th century, in which there are noted, for example: “Turkish red leather, 8 red straps [the kind used to hold a scabbard with a sword by the belt], acidified sabers, golden embroidered saddle cloth, golden silver-covered saber” and many others. These stores also listed a striking number of items made of tin, brass and silver, especially silver spoons. Turkish, Turkmen and old silk carpets are also mentioned in large numbers with kilims, Persian and Turkish silk belts, simple and morocco embroidered leather and fabrics such as: “kamlot, Indian linen, Tartar muchaier, bagasia, Turkish muchaier, tabin”.

Since trade with the East was dominated by Armenians, the entire department of eastern goods, i.e.: carpets, gold embroidery, patterned applications, weapons decorated with precious metals and precious stones, horse tacks, sajadaks, kalkans, were called "Armenian goods" in Lvov.

Armenian trade was able to develop so efficiently thanks to convenient legal regulations. The merchants of Stanisławów, for example, were exempted from paying tolls and customs duties in all Potocki's hereditary estates in the 18th century - and in the 18th century the lands of almost the entire Pokucie region belonged to this family - so the Armenians strove hard to obtain the citizenship of Stanisławów and settled there in large numbers.

In the eighteenth century, Armenian trade gradually developed an organized character. Grzegorz Nikorowicz, who conducted "Turkish trade" in Lvov, was sent by King August III to Persia in 1746 to purchase goods. His son, Szymon Nikorowicz, already had an agency in Istanbul that made purchases for his stores in Poland. On the basis of the document - Registry of Persian, Turkish and Lvov's Goods - drawn up in 1764 by Szymon Nikorowicz, we know that he sent, for example, saddles, belts,tapes, fasteners, halters, hilts and shackles for cutting weapons. The Nikorowicz department store in Lviv lost its importance after the First Partition of Poland, when Polish Armenians had already completely integrated into Polish society.

Parallel to the development of Armenian trade and crafts in Poland and the strengthening of the social position of Armenians, the differences in customs between Poles and people of Armenian descent were becoming blurred. Armenians, for example, wore Polish clothes as early as the 17th century, as evidenced by the lists of movable property of Armenian merchants from Zamość, which mention: summer jackets, caftans, ferezias, giermak and kołpak, gold buttons and belts, żupans, delia and kontusz. In Armenian shops there were: kabaty, robe loops, wide Angura belts, "gentleman's velvet cap" and "sable cap with ears".

The Armenians in Lviv quickly made enormous fortunes on trade with the East, which even for the very rich Polish burghers, was something completely exceptional. Material wealth made it possible to express a truly Eastern vanity, shown in exquisite clothes and gold jewelry, often decorated with diamonds and pearls; splendor of weapons. This luxury and panache, which the Lwów patriciate of Polish descent could not afford, provoked unfavorable comments. In 1682, Stanisław Karwowski, the city instigator in Lviv, sued Jan Jaśkiewicz, an Armenian, for arranging too lavish wedding ceremonies for his daughter. Her husband, Mr. Borykowicz, an Armenian from Kamieniec Podolski, was accused of wearing expensive attire that seemed highly inappropriate. From this document we learn that Armenian women dressed not only in "justaucorps, coats, hats, gloves", but also in "dresses alias skirts, ancras, jups" made of "rich fabric of golden threads, serma, lama, velvets and other expensive matter." They also had furs of "sable, lynx [...]” - in general the most expensive and best fur. According to the quoted account, the scandal was caused by the use of ostrich feathers as an accessory to the diamond crown on bride’s head, to which, according to the councilor of Lviv, only the spouses of magnates were entitled. A bride wearing “a golden robe with an inderak (type of skirt) which cost 12 hundred zlotys, stockings and embroidered shoes which cost nearly 200 zlotys” was even harshly criticized. On the other hand, "Mr. Bobrykiewicz himself, apart from other clothes, had a robe all lined with sables with gold buttons and precious stones, and when it came to dancing [...] another robe made of Dutch cloth, all lined with llama, he put on even shoes [ ...] embroidered with gold".

During their centuries-long stay in Poland, the Armenians have become fully integrated into society, which resulted, among other things, in the fact that their once independent and original work became part of Polish art. Similar processes in the Armenian diaspora, although to a much lesser extent, were also taking place in other European countries. At the same time, Western art could not free itself from the tradition and influence of Armenian art and culture, to which it owed a lot. Certainly, in the work of bringing the civilizations of the East and the West closer, the Armenians played a significant role as Christians living in Asia, who enriched their own works with ornaments taken from the art of Islam and passed them on to European art.

The Armenians played a special role in transferring the features of Persian and Turkish art to Poland and in raising interest in the Orient in Polish society, and - what is very important - sensitivity to a type of art foreign to European culture. Thanks to new research, based on published source materials, it is certainly possible to slightly reduce the importance of war gains and Sarmatian tradition in broadening the interest in Islamic art in Poland, to the benefit of Armenian trade. It can be assumed that Christians dressed in Persian style - Armenians had an influence on the formation of the basic features of the national-attire-cut in Poland; thanks to their commercial activity, eastern belts were imported, which became an indispensable part of this attire, and the interiors of Polish residences were decorated with carpets, tapestries and silk fabrics with Persian and Turkish motifs.

Polish Armenians in the 20th century

The 20th century did not initially bring any significant changes to Polish Armenians. Most of them still lived in the south-eastern areas of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, now known as Eastern Galicia, which was part of the Austrian partition. Their number was estimated at about 5,000. More or less 1,000 of them lived in nearby Bukowina, in which they settled during the 19th century. Probably as many Armenians came from Turkey at the beginning of the interwar period - at least those who did not die during the genocidal actions organized by the Turkish authorities in 1915. There were also refugees from Russia, which was under revolution.

Relatively many Armenians belonged to the landed gentry and, as an elite, occupied appropriate positions in the social hierarchy. Most of them formed the middle class in cities, being entrepreneurs, officials, teachers or freelancers. There were also merchants and craftsmen.

They were religiously distinguished because they had their rite within the structures of the Catholic Church. They belonged to the Archdiocese of Lviv of the Armenian Catholic Rite, headed from 1902 by Archbishop Józef Teodorowicz, who was also an outstanding Polish politician. Their parishes were located in Lvov, where there was an Armenian cathedral from the 14th century, and also in Brzeżany, Stanisławów, Tyśmienica, Łysiec, Horodenka, Śniatyn and the largest one in Kuty. In addition, the parish in Czerniowce in Bukowina, which in the interwar period was part of Romania, should be mentioned.

At that time, Armenians in Poland earned great prestige due to their merits in the field of politics, economy, science and art. They were usually very Polonized. Maybe apart from a rather conservative cluster in Kuty. In general, however, they wanted to maintain their separateness to some extent. Therefore, they founded the Archdiocesan Union of Armenians and published a magazine called "Posłaniec św. Grzegorza" (eng. Messenger of st. Gregory).

During World War II, Armenians participated in battles. They had representatives probably in all Polish military formations.

When the areas of south-eastern Poland went under Soviet occupation, the local Armenians, especially those from the former elites, were persecuted. Many were arrested, some were sent to Siberia. However, during the German occupation, many who had a rather exotic appearance had to prove that they were not Jewish. But thanks to the fact that there were people of such appearance in this area, it was possible to save some Jews by providing them with certificates confirming their Armenian origin. In addition, quite a few Armenians were murdered by Ukrainian nationalists, carrying out ethnic cleansing.

Immediately after the war, repressions fell on the Armenian clergy. Fr. Dionizy Kajetanowicz, administrator of the Archdiocese of Lvov, was sent to a labor camp, where he died in 1954. The others were not spared various harassment either, but eventually they were allowed to leave for Poland within the new borders.

Almost all Armenians moved there. Only a small group in Kuty remained. They most often chose large cities for their new place of residence: Kraków, Warsaw and Gdańsk. Many of them settled in Upper and Lower Silesia: in Katowice, Bytom, Gliwice, Opole, Wrocław, Wołów, Oława. Pastoral centers of the Armenian rite were established in Kraków, Gliwice and Gdańsk, but for various reasons they failed to revive its tradition, or at least to sustain it. They stopped looking for spouses among the Armenians and mixed marriages became the rule. There was a clear disintegration of this community.

From 1980, the rebirth of Polish Armenians began. At that time, a Circle of Interest in Armenian Culture was established at the Kraków branch of the Polish Ethnological Society, and soon similar ones were established in Warsaw and Gdańsk. After 1990, other organizations and foundations were established.

Later that year, Armenians from Armenia, affected by the earthquake, Karabakh war and economic crisis, began to settle in Poland, and later also from other parts of the former Soviet Union. This new emigration contributed significantly to the revival of the Armenian community in Poland.

The emerging new legal conditions under the Act on National and Ethnic Minorities and Regional Language gave the Polish Armenians the status of a national minority. A Joint Commission of the Government of both National and Ethnic Minorities was established, in which the interests of minorities are represented by people elected by them. In 2005, Maciej Bohosiewicz was elected by the Armenian community as the first representative of the Armenian minority, and soon he became the representative of all minorities in the Joint Commission. This situation contributed to the systematization of the activities of the Armenian diaspora and began the dynamic development of Armenian organizations and advocacy.